The Dual Edges of Catharsis and Retraumatization

I. Introduction

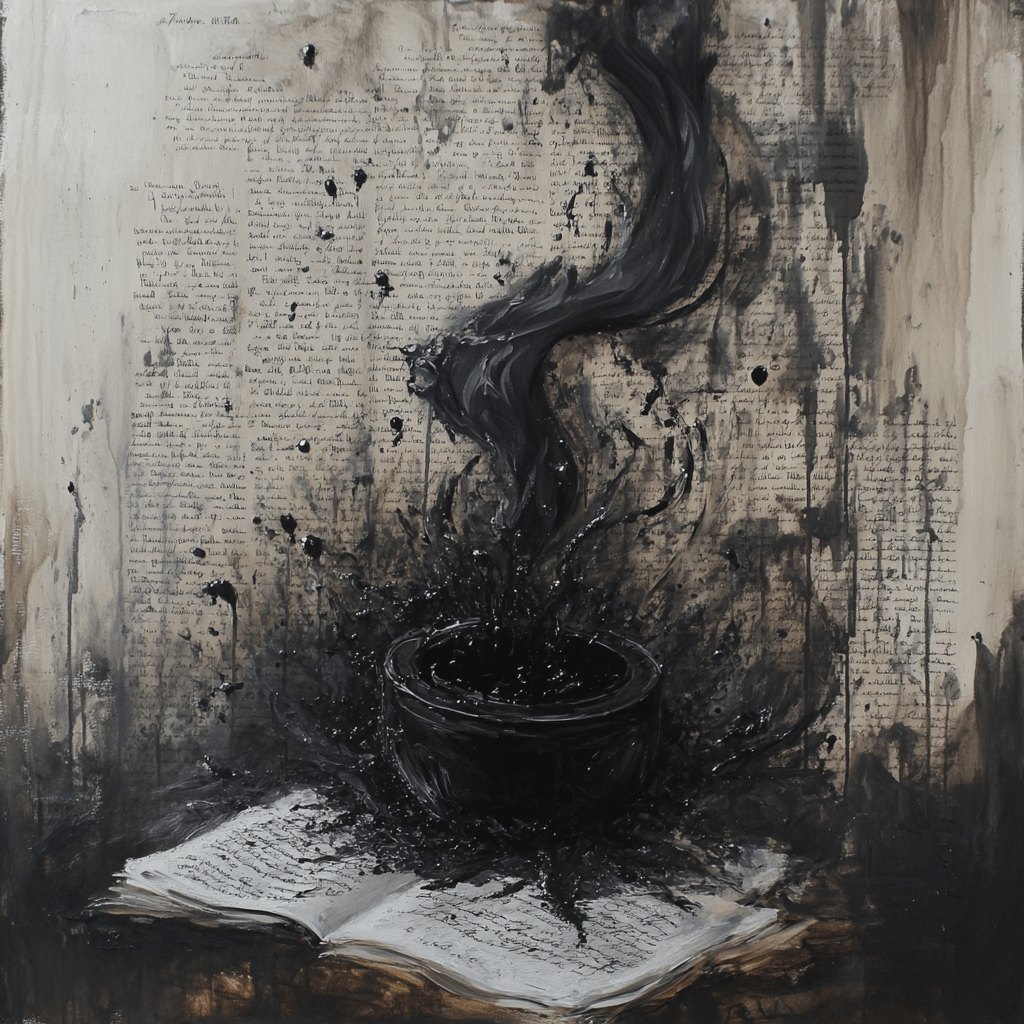

Memory is not a film reel playing on repeat, but a phantom limb that aches with a life of its own.” This sentiment, echoing the disquieting nature of recollection, underscores the precarious ground upon which any attempt to write about grief must tread. Writing, in its essence, is a form of memory made manifest, a tangible inscription of the intangible. Yet, within the realm of grief, this act of inscription becomes a double-edged sword, capable of both healing and wounding. The pen, wielded in the pursuit of catharsis, may inadvertently reopen the very wounds it seeks to mend.

Writing about grief presents a complex interplay between the potential for cathartic healing and the risk of retraumatization, requiring a nuanced understanding of how to navigate this duality within historical, social, and cultural contexts. This is not a simple equation, nor does it yield easy answers. The act of translating the raw, visceral experience of grief into the ordered structure of language is fraught with inherent dilemmas. Does the attempt to capture the ephemeral nature of sorrow inevitably lead to its distortion? Can the very act of articulation, meant to provide solace, instead become a source of renewed pain? These are the enduring questions that haunt the writer who dares to confront grief on the page.

This essay will explore the dual nature of writing as it intersects with grief, delving into the therapeutic potential of expressive writing while acknowledging the very real risks of retraumatization. We will examine the delicate balance between expression and avoidance, the challenges of navigating individual variability, and the profound influence of historical, cultural, and social contexts. We will consider the philosophical implications of capturing grief in language, exploring the limits of articulation and the elusive nature of memory. Throughout this exploration, the central tension between writing’s role as both a therapeutic tool and a potential source of retraumatization will remain at the forefront of our analysis. This is not an attempt to provide definitive solutions, but rather to illuminate the inherent complexities and uncertainties of writing about grief, to grapple with the enduring questions that arise when language confronts the depths of sorrow.

II: The Therapeutic Potential and Perils of Writing

The therapeutic potential of writing has been widely explored, with research suggesting that expressive writing can lead to both emotional and physical health benefits. The act of putting grief into words, of translating the raw experience of loss into a narrative structure, can provide a sense of control and understanding. Yet, this very process of articulation can also be a source of retraumatization, as the writer is forced to confront and relive painful memories. The inherent tension between these two possibilities lies at the heart of the challenge of writing about grief. Can writing truly serve as a therapeutic tool without simultaneously deepening the wounds it seeks to heal? This is the enduring question that must be addressed with both sensitivity and critical awareness.

The Case for Writing as Therapy

Writing, when approached with intention and care, can serve as a powerful tool for processing grief. Research by Pennebaker and others has demonstrated that expressive writing can lead to positive outcomes, including improved emotional regulation, enhanced immune function, and reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety. The act of articulating grief, of giving shape to the amorphous experience of loss, can facilitate emotional processing and cognitive restructuring. By translating raw emotions into language, the writer gains a measure of distance from the experience, allowing for greater objectivity and understanding. Writing can also serve as a form of self-reflection, a means of exploring the deeper meaning and significance of loss. The act of putting grief into words can be a way of making sense of the experience, of finding meaning in the midst of suffering. Furthermore, writing can facilitate social connection, providing a means of sharing one’s grief with others and receiving support. The act of writing can be a way of breaking the silence that often surrounds grief, of reaching out to others and finding solace in shared experience.

The Perils of Writing as Therapy

While writing can be a powerful therapeutic tool, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations and potential risks. Writing, in its essence, is a form of representation, an attempt to capture the complexities of experience through the imperfect medium of language. The act of translating grief into words inevitably involves a degree of simplification and distortion. The nuances of emotion, the subtle shifts in feeling, the ineffable sense of loss—these may defy easy articulation. Furthermore, the act of writing about grief can be emotionally taxing, requiring the writer to confront and relive painful memories. This can lead to emotional overload, rumination, and even misinterpretation of the experience. Writing, if not approached with care, can become a source of retraumatization, deepening the wounds it seeks to heal. It is essential to recognize that writing is not a panacea for grief, nor is it a universally effective solution. For some individuals, particularly those who have experienced significant trauma, writing about grief may be counterproductive, leading to increased distress and psychological harm.

Historical, Cultural, and Social Contexts

The interplay between writing and grief is not a modern phenomenon; it is deeply rooted in human history and culture. Ancient rituals, from the Egyptian Book of the Dead to the Greek laments, demonstrate the human impulse to articulate grief through written and performative expression. These traditions often served as a means of communal mourning, providing a structured framework for processing loss. In contrast, the rise of grief memoirs in the 20th and 21st centuries reflects a more individualized approach to mourning, where personal narratives of loss are shared with a wider audience. However, even within these seemingly personal expressions, cultural and social expectations exert a powerful influence. For instance, the Victorian era’s emphasis on elaborate mourning rituals and the suppression of raw emotion shaped how grief was expressed in literature and personal writings. Similarly, certain cultures may maintain a silence around specific forms of loss, such as miscarriage or suicide, which can hinder the therapeutic potential of writing by imposing unspoken boundaries on expression.

The influence of cultural silence and societal expectations on writing’s effectiveness cannot be overstated. When grief is shrouded in stigma or taboo, the act of writing about it can become an act of rebellion, a way of breaking the silence and reclaiming agency. However, it can also lead to increased isolation and shame, particularly if the writer’s experiences are not validated or understood by their community. Societal expectations regarding the “appropriate” duration and intensity of grief can also create pressure to conform to prescribed narratives of healing, which may undermine the authenticity and therapeutic value of writing.

The digital space has further complicated the relationship between writing and grief. Social media platforms provide new avenues for sharing grief, allowing individuals to connect with others who have experienced similar losses. However, the curated nature of online expression, the pressure to perform grief for an audience, and the potential for public scrutiny can also lead to a sense of inauthenticity and exploitation. The line between personal catharsis and public spectacle blurs, leaving the writer to navigate the ethical implications of sharing their most vulnerable experiences in a world that often treats suffering as a commodity. The digital echo chamber, with its potential for both amplified support and amplified judgment, adds another layer of complexity to the already fraught terrain of writing about grief.

Philosophical Interlude

When attempting to capture grief in language, one is immediately confronted with the question: can words truly embody the lived experience of sorrow? Is language a tool that faithfully reflects the world, or does it construct its own reality, subtly altering the very experience it seeks to convey? Does language offer a clear path to understanding, or does it inherently obscure the depths of human emotion? Perhaps language is a series of signposts, guiding us towards meaning, but ultimately incapable of fully capturing the essence of being. Or is it more akin to a game, its rules and structures creating a framework within which we can play, but never fully grasp the underlying reality? The very act of translating grief into words raises the enduring question: can language ever truly represent the raw, visceral experience of loss, or is it destined to remain forever an approximation, a shadow of the lived reality?

Furthermore, how does the nature of memory influence our attempts to articulate grief? Is memory a static archive, a fixed record of past events, or is it a dynamic, ever-changing process, constantly being rewritten and reinterpreted? Do our memories unfold like a linear narrative, a series of discrete moments strung together in a chronological sequence? Or are they more akin to a flowing river, a continuous stream of consciousness, where past, present, and future merge and overlap? Does the act of writing about grief preserve memory, faithfully recording the past? Or does it transform memory, shaping it into a narrative that serves the needs of the present self, a reconstruction that blurs the lines between recollection and invention? Is memory a series of discrete images, easily recalled and described, or is it a fluid, continuous movement, a duration that defies capture? And if memory itself is a process of becoming, how can language, a system of fixed signs, ever hope to represent its elusive nature? These questions highlight the inherent limitations of language and the elusive nature of memory, adding layers of complexity to the already fraught terrain of writing about grief.

Perhaps the act of writing about grief is, at its heart, a practice in cultivating inner fortitude. Can the disciplined use of language, the careful crafting of narrative, serve as a means of strengthening one’s emotional resilience in the face of loss? Or does the very attempt to impose order on the chaos of grief risk stifling the raw, authentic expression of sorrow? Is it possible to find virtue in the act of articulating pain, to discover a form of self-mastery amidst the ruins of loss?

Consider, too, the weight of individual responsibility in the face of grief. If existence is fundamentally without inherent meaning, does the act of writing become a way of creating meaning, of asserting one’s freedom in the face of an indifferent universe? Or is this a futile endeavor, a mere illusion of control in a world governed by chance and necessity? Does the writer, in their attempt to give shape to grief, assume the burden of crafting a narrative that justifies the pain, that finds purpose in the void? And how does this pursuit of meaning intersect with the ever-present risk of retraumatization, the potential for language to reopen wounds rather than heal them?

What, then, of the lived experience of grief, the subjective encounter with loss that defies objective analysis? Can writing serve as a means of delving into the depths of this experience, of exploring its nuances and complexities through careful observation and reflection? Or does the very act of reflection create a distance, a separation between the writer and their grief, transforming lived experience into a mere object of contemplation? Is it possible to truly capture the essence of sorrow through language, to convey the visceral reality of loss without reducing it to a mere abstraction? And how does this pursuit of authentic expression navigate the delicate balance between catharsis and retraumatization, between the therapeutic potential of writing and its inherent risks?

These questions, these unresolved tensions, underscore the inherent dilemma of writing about grief. The act of articulation can be a powerful tool for healing, a means of processing trauma and finding solace in shared experience. Yet, it also carries the potential for harm, the risk of reopening old wounds and deepening the pain of loss. The challenge lies in navigating this duality, in finding a way to write about grief that honors its complexity and ambiguity, that acknowledges its power to both heal and wound.

III. Navigating the Duality: Expression, Avoidance, and Control

Having explored the inherent tensions between writing’s therapeutic potential and its risks of retraumatization, we now turn to the practical considerations of navigating this duality. This section delves into the strategies and approaches that writers can employ to harness the healing power of expression while safeguarding against the deepening of pain. We will examine the delicate balance between confronting grief and avoiding its overwhelming intensity, and consider how individual variability and ethical considerations shape the writing process.

The Healing vs. Harm Debate

Can writing truly heal without deepening pain? This question lies at the heart of the debate surrounding the therapeutic use of writing in the context of grief. While expressive writing has shown promise in facilitating emotional processing and reducing psychological distress, it is essential to acknowledge the potential for harm, particularly for individuals who have experienced significant trauma. The act of writing about grief can be akin to reopening a wound, forcing the writer to confront and relive painful memories. This can lead to emotional overload, retraumatization, and even a reinforcement of negative thought patterns. The challenge lies in finding a way to harness the therapeutic potential of writing while mitigating the risks, in creating a space where expression can lead to healing without exacerbating the pain.

One approach is to view writing as a form of controlled trauma reliving. Guided writing protocols, with specific prompts and time limits, can provide a structured framework for processing grief, allowing the writer to engage with painful memories in a safe and controlled manner. Trauma-informed writing practices emphasize the importance of pacing, grounding techniques, and self-regulation strategies to prevent emotional overwhelm. Ethical considerations are paramount, particularly when working with individuals who have experienced significant trauma. The writer’s autonomy and agency must be respected, and the writing process should be approached with sensitivity and care, ensuring that it does not become a source of further harm.

Individual Variability and Limits of Integration

It is crucial to acknowledge that writing is not a universally effective tool for processing grief. Grief is a deeply personal experience, shaped by individual circumstances, personality traits, and coping mechanisms. What works for one person may not work for another. Some individuals may find solace in the act of writing, using it as a means of processing emotions and finding meaning. Others may find that writing exacerbates their pain, leading to increased distress and rumination. The effectiveness of writing as a therapeutic tool is further complicated by the limits of integration. Even when writing is beneficial, it may not fully resolve the complexities of grief. Some aspects of loss may remain unassimilated, lingering in the shadows of consciousness, defying easy articulation.

The pursuit of closure through writing can also be problematic. The desire to create a neat, coherent narrative of grief can lead to a false sense of resolution, a premature attempt to impose order on the chaos of loss. Grief, in its essence, is an ongoing process, a journey without a clear destination. Some pain may remain unwritten, some memories may resist articulation. This does not signify failure, but rather an acceptance of the inherent limitations of language and the enduring mysteries of grief. It is essential to recognize that there are alternative pathways to healing, forms of expression and processing that lie beyond the written word. The pursuit of wholeness may require a multifaceted approach, integrating writing with other therapeutic modalities, such as art, music, or movement.

Expression vs. Avoidance: A Complex Relationship

The bond between expression and avoidance in grief is both intricate and delicate. While confronting the raw ache of loss through words is vital, guarding against the tidal wave of sorrow is just as critical. Writing about grief demands a tightrope walk—a dance between unearthing painful memories and shielding oneself from their jagged edges. Tools like focused prompts, vivid metaphors, timed pauses, and intentional shifts in focus can craft a sanctuary for this tender work. Focused prompts offer a lifeline, guiding the writer to explore grief’s facets with purpose, while metaphors weave emotions into images, sidestepping the need for stark detail. Timed pauses and deliberate distractions, meanwhile, act as anchors, pulling the writer back from the brink of overwhelm to a place of calm and control.

Self-kindness and adaptability are the heartbeat of a sustainable writing practice. Writers must tune into their limits, adjusting their approach when the weight grows too heavy, and place self-care above all. Grief-writing isn’t a rigid mold—no single path fits every soul. What heals one may unravel another. The goal is a rhythm that feels both cleansing and bearable. A therapist’s steady hand can light this winding road, offering wisdom, encouragement, and a mirror to reflect the writer’s progress. They can untangle buried trauma or quiet lurking distress, fostering coping strategies that endure.

Striking a balance between expression and avoidance is the crux of grief-writing. Focused prompts carve a clear trail through loss’s wilderness, while metaphorical language paints feelings in bold strokes, sparing the writer from reliving every wound. Timed pauses and mindful detours serve as breaths of relief, keeping emotional floods at bay. The aim? A haven where grief can speak yet not consume.

Self-compassion and flexibility fuel this practice’s vitality. Writers must bend with their needs, know when to ease up, and cherish their well-being. Grief’s terrain varies wildly—no two journeys mirror each other. The writing must echo that singularity. A counselor’s guidance can be a compass here, not to command the pen, but to empower the writer, helping them navigate grief’s maze and forge a truce with their pain.

Literary Analysis

Incorporating detailed analysis of literary works that exemplify writing, grief, and trauma themes provides valuable insights into the complexities of navigating this duality. By examining how authors across time and cultures grapple with these themes, we gain a deeper understanding of the challenges and possibilities of writing about grief. Consider three striking examples: an ancient Greek tragedy, a Native American novel, and a contemporary Japanese memoir, each a window into the soul’s tangle with loss.

Picture Sophocles’ Antigone (circa 441 BCE), where grief ignites rebellion and writing becomes defiance. Antigone, mourning her brother Polynices, pens her fate in actions louder than words, burying him against King Creon’s edict. Her obsessive devotion spirals into tragedy, showcasing how grief can fuel a destructive fixation, etching trauma into her family’s lineage. This ancient Greek lens reveals retraumatization’s cruel echo—how clinging to the dead can chain the living to ruin, a stark warning carved in timeless verse.

Now shift to Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony (1977), a Native American tapestry of healing through story. Tayo, a World War II veteran, bears the weight of cultural and personal trauma—grieving lost kin and a fractured Pueblo identity. Writing here is a sacred weave, as ceremonial narratives and metaphors (spider webs, rain) mend his shattered spirit, offering a path from despair to renewal. This Indigenous reclamation proves writing’s transformative fire, a balm against historical wounds that restores both self and community.

Finally, step into Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police (1994), a Japanese elegy for loss in a dystopian haze. On an island where objects—and memories—vanish, a novelist chronicles grief as resistance, penning tales to preserve what fades. Her haunting metaphors (disappearing roses, silent rivers) voice the unspeakable ache of erasure, yet her craft teeters on the edge of oblivion, reflecting trauma’s quiet theft. This modern parable captures the fragile dance of expression and avoidance, where writing fights to hold ground against a tide of forgetting.

Peering through these diverse lenses, we grasp grief-writing’s kaleidoscopic nature. We see authors battle this beast—Sophocles with fatal resolve, Silko with restorative grace, Ogawa with defiant fragility—and harvest their hard-won truths. These stories don’t just illuminate writing’s dual edge—catharsis and wound—but beckon us to map our own grief-laden trails, offering torches to light the way. By analyzing these works, we can see how different authors have approached the challenges of writing about grief, what strategies they have employed, and what insights they have gained. These analyses not only illustrate the duality of writing as both catharsis and retraumatization but also provide a framework for readers to reflect on their own experiences with grief and writing.

Conclusion

We’ve sharpened our understanding of the twin blades of grief, uncovering writing’s dazzling promise as a healing salve and its lurking threat of tearing wounds anew. Spinning sorrow into words can unlock emotional release and rewire tangled thoughts, yet it teeters on a knife-edge, requiring a deft weave of expression and restraint. We’ve traced the threads of history, culture, and society, pondered the philosophical weight of pinning grief to the page, and confronted the frail limits of language and memory. The wild dance of individual differences and the call for ethical care shine through, demanding a tailored, tender touch when wielding the pen against loss.

Grief-writing isn’t a universal cure. It brims with gifts—catharsis, clarity—yet bristles with dangers, especially for those still drowning in raw pain. The taut pull between seeking solace and risking relapse creates a high-stakes tightrope, urging us to cherish its healing spark while dodging its hidden thorns. The haunting riddle persists: how do we wield language as a lifeline without slashing open sorrow’s scars?

As we weigh writing’s tangled role in grief and trauma, we’re summoned to craft a bespoke path—one that bows to expression’s redemptive might while bracing against retraumatization’s bite. Each grief trek is a lone road, and writing must mirror that solitary pulse. It’s a voyage of uncharted depths, a quest to map sorrow’s wild shores. It craves self-kindness, nimble shifts, and a bold embrace of loss’s murkiness. Can writing cradle grief’s full weight without drawing fresh blood? This enigma, like grief itself, lingers unanswered. Grief-writing isn’t about nailing down truths—it’s about wrestling with the eternal questions, standing as a raw testament to loss’s labyrinth.

Grief stalks like a shadow, both ghost and void, a whisper of what was, a wail for what might be. Writing, chasing this fleeting phantasm, becomes a twilight waltz, a fragile pirouette to honor the departed without slipping into despair’s abyss. And in that tender chase, in reaching for the unsayable, we don’t grasp closure—we unveil a fierce, unshakable echo of the human spirit’s grit to press on.