The Shifting Nature of Grief and the Challenge of Writing About It

I. Introduction: The Ephemeral Shape of Grief

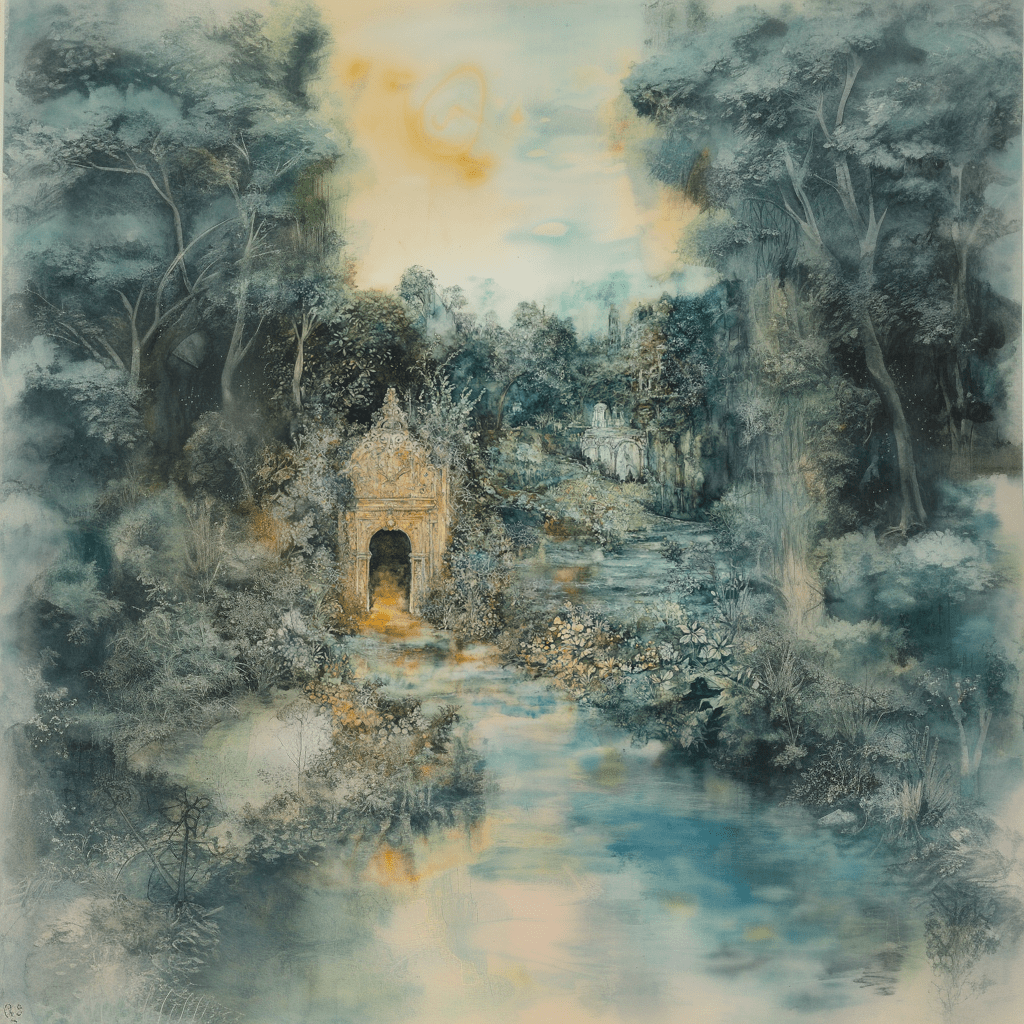

The antique music box, a relic from childhood, once played a tune that evoked the sharp, clear image of my grandmother’s garden—roses bowed under the weight of dew, the air thick with the scent of damp earth, her voice a quiet thread of humming woven into the morning. Now, when I wind the key, the melody wavers, the garden blurs, and her humming is no more than an echo lost in the distance of time. Grief, like this tune, shifts and fades, its edges softening, its essence transforming in ways that defy memory’s steadfast claims. What was once a landscape etched in stark lines of sorrow now resembles a watercolor, its hues bleeding into one another, its form elusive.

Writing about grief is fraught with difficulty because grief itself is unstable, resistant to static representation, and often defies narrative coherence. It is a shape-shifter, a phantom that refuses to be captured, a current that surges and recedes with no warning to a rhythm all its own. To attempt to capture it in the fixed frame of language is to chase a shadow, to try and hold water in cupped hands. The writer, then, stands at the threshold of an impossible task, caught between the pull of order and the chaos of loss, between form and formlessness, between the need for meaning and the weight of meaninglessness, all seemingly framed by the cultural lens of mourning. We write to impose structure on what refuses to be structured, to carve sense from the senseless, to wrest the ineffable into words. Yet grief, in its essence, resists such tidy resolutions and precise articulations. How does one build a monument of language within a landscape that time itself is constantly dismantling?

II. The Fundamental Instability of Grief

The world is a river, not a still pond. Experiences, emotions, and perceptions flow and transform, their shapes constantly shifting. What seems immutable today may fade into a distant memory tomorrow, only to resurface unexpectedly. Time, rather than a linear progression, is a series of overlapping moments, each influencing and altering the others. Reality is not a fixed construct but a dynamic interplay of forces, a constant negotiation between presence and absence, certainty and doubt. The mind, like a restless sea, is in perpetual motion, its currents carrying fragments of the past, present, and future, weaving them into a tapestry of ever-evolving understanding.

Grief, in particular, embodies this fluidity. It does not move linearly; what is crushing today may feel distant tomorrow, only to return unexpectedly, like a tide that ebbs and flows, its strength unpredictable. The heart, once a vessel overflowing with sorrow, may find brief respite, a moment of calm in the storm. But this is a deceptive peace, for grief is a shape-shifter, its presence elusive, its return inevitable. It is a dance between presence and absence, a constant negotiation between the searing immediacy of loss and the slow, almost imperceptible erosion of its sharpness over time. The wound may begin to scar, but the memory of the blade remains, a phantom ache that can be reawakened by a scent, a song, a forgotten photograph.

If experience is a river, ever-changing and defying capture, then memory is its unreliable mapmaker, charting a course that shifts with the tides of time. The very fluidity of experience undermines memory’s attempt to create a faithful record. What we remember is not a fixed reality but a reconstruction, a palimpsest overwritten by time, emotion, and the ceaseless flow of new experiences. The best we get is a map of the rough shape of the river, not the river itself; a memory of the rough shape of an experience, not the experience itself.

Memory is less about accurately recalling the past and more about the interplay between past experiences and present perceptions. The act of remembering is not a passive retrieval but an active creation, a process shaped by our current emotions, desires, and perspectives. The past is not a fixed entity but a series of potential memories, each waiting to be activated and reconfigured by the present moment. This understanding highlights the inherent unreliability of memory, its tendency to reshape and reinterpret the past in ways that serve our current needs and desires.

Grief, in particular, reveals memory’s inherent unreliability. It reconstructs grief in ways that shift with time, sometimes softening its sharpest edges, blurring the painful details, offering a semblance of comfort. At other times, it sharpens the edges, amplifies the sorrow, reminding us of the unbearable weight of loss. The problem of retrospective narration, then, becomes a central challenge for the writer of grief: can we ever truthfully write about a past grief without imposing the perspective of the present self? Is it possible to separate the memory of the event from the memory of the feeling, to capture the raw, unfiltered experience of grief without the lens of time distorting our vision? The past, it seems, is not a fixed point, but a constantly shifting landscape, forever altered by the winds of the present.

Where does that leave us then, the cartographers of grief? Words, those carefully chosen symbols, are fixed, immutable, while grief, filtered through the lens of fallible memory, remains a river, ever-flowing, ever-changing. The act of writing, then, risks betraying the very essence of the experience, fossilizing what should remain in flux. To describe the searing pain of loss is to attempt to capture lightning in a bottle, to contain the boundless within the finite. Language, in its attempt to grasp the enormity of grief, becomes a cage, trapping the wild, untamed spirit of sorrow within its bars. Yet, it is in this very act of articulation, in this struggle to find the right words, that we confront the paradox of grief: the need to express the inexpressible, to give voice to the voiceless. Language, though ultimately insufficient, is the only tool we have, a flawed instrument in the hands of a wounded soul.

III. The Structural Dilemma: Order vs. Chaos

Grief does not unfold neatly. It lurches, stops, stutters. One moment, clarity—the sharp sting of absence. The next, fog—memories slipping through grasping fingers. It is not a story with a beginning, middle, and end. It is scattered pages, torn from different books, shuffled by an unseen hand. To impose order is to misunderstand. Fragments unfinished sentences thoughts that loop back without warning a conversation cut off mid-sentence with no chance to finish a room entered without remembering why a thought that vanishes the moment it arrives this is grief recursive erratic a broken reel of memory stuttering forward then back full of gaps that refuse to be filled a story without sequence a map with no landmarks a pulse that skips and stumbles but never quite stops.

Yet, this approach presents a challenge: such structures, while true to the experience of grief, may alienate readers seeking coherence or catharsis. The reader, accustomed to the familiar arc of narrative, may find themselves adrift in a sea of disjointed fragments, unable to find a foothold, a sense of resolution.To read of grief in its rawest form is to step into a building somewhere between demolition and repair, without scaffolding, without certainty. Some will understand. Others will be lost.

Traditional forms of mourning, such as the elegy, offer a structured approach to grief, providing a framework for expressing sorrow and finding solace.

“There was a time when your voice lived in the air, woven into the hush of morning, the hum of evening. Now, the silence folds itself around me, soft, inevitable, full of echoes. You were never meant to stay in one place—you have only changed direction, like the moon moving the ocean without touch, like a melody lingering after the last note fades. And I will call this love, still.”

These forms, with their lyrical beauty and orderly progression, offer a sense of comfort, a way to contain the chaos of grief within the boundaries of art. Yet, they also risk sanitizing the messiness of grief, smoothing out its jagged edges, transforming it into something beautiful, but ultimately, less authentic. The tension between form and authenticity becomes a central dilemma: does art require structure, or should grief be left raw and jagged on the page, a testament to the untamed nature of sorrow.

The impulse to shape loss into something meaningful, to find a narrative arc in the chaos of grief, is a deeply human desire. We seek to impose order on the disordered, to find a sense of purpose in the midst of meaninglessness. Writing, then, becomes a means of imposing narrative on the unnarratable, a way to create a semblance of control in the face of uncontrollable loss. This very act of imposing narrative raises an uneasy question: does writing about grief provide solace, or does it merely trap an evolving experience in a static frame, freezing a moment in time, preventing the natural flow of sorrow? Is it possible to find meaning in grief without betraying its inherent ambiguity, its resistance to tidy resolutions? Often for us to get a good look at grief it must be broken down to the point where it is no longer the grief we were looking at in the first place; and so we can never get a good look at things as they are. It is perhaps in fragments that we can see the whole of grief at once and it is reveals to us what it looks like, but it is in the whole with parts obscured from a moment’s gaze that the object discloses what it is.

You’re welcome! Let’s proceed to the next section: “IV. The Burden of Resolution.”

V. Cultural and Social Expectations: The Language of Mourning

The act of writing about grief is not merely a solitary endeavor but one deeply embedded within a web of cultural and social expectations. From the established rituals that guide mourning to the unspoken pressures to find meaning and resolution, the writer navigates a complex landscape. From the diverse cultural scripts that shape our understanding of grief, to the societal pressures that demand resolution and meaning, and ultimately the ethical dilemmas posed by the commodification of sorrow in our modern age.

Cultural scripts for grief vary widely, from the restrained silence of some societies to the wailing lamentations of others. These traditions, passed down through generations, shape the way we express grief and influence the reception of grief literature. Writers, then, must navigate a complex terrain, balancing their personal experiences with the expectations of their cultural context. How much should grief be made palatable for an audience? How much should it conform to the established norms of mourning? The ethical question of making suffering readable becomes a constant negotiation, a delicate dance between authenticity and cultural acceptance.

The writer’s struggle to balance personal truth with societal expectations is a constant tension. Grief, though deeply personal, is also a social experience, shaped by the collective understanding of loss. Writers must decide how much of their raw, unfiltered grief to share, how much to temper with the language of cultural propriety. The question becomes: how much should grief be made palatable for an audience? How much should it conform to the established norms of mourning? The ethical question of making suffering readable becomes a constant negotiation, a delicate dance between authenticity and cultural acceptance.

Readers often seek comfort, resolution, or transformation in grief narratives, mirroring societal expectations around healing. We are drawn to stories of overcoming, of finding light in the darkness, of emerging from sorrow stronger and wiser. Yet, the honest portrayal of grief often defies such tidy resolutions. What if there is no resolution? What if the pain lingers indefinitely, a constant companion, a shadow that refuses to dissipate? The writer, then, stands at a crossroads: to conform to these expectations, to offer a comforting fiction, or to risk alienating the reader with a portrayal of grief that is unvarnished, unresolved, and unsettlingly real.

The weight of meaning-making presses heavily upon the writer. Society demands that loss serve a purpose, that it birth growth, wisdom, or a renewed appreciation for life. Grief, we are told, is a crucible, a catalyst for transformation. But what if grief is simply grief? Raw, unyielding, unknowing—a landscape devoid of easy lessons, barren of silver linings? The writer faces a stark choice: to succumb to the demand for redemption, to impose a narrative of meaning upon their experience, or to resist, to portray grief in its unadorned, unresolvable form.

Beyond the pressure to provide resolution or extract meaning, there lurks the insidious tendency to pathologize grief that deviates from prescribed timelines or trajectories. Grief that lingers, intensifies, or refuses to conform is labeled “complicated” or “pathological.” This medicalization of sorrow further isolates the bereaved, silencing their authentic experiences, adding the weight of a diagnosis to the already heavy burden of loss. So, grief is not only expected to have a demarcated ending and be used to transform one’s life, but now, it can be done ‘wrong,’ resulting in a label, a pathology.

When, then, does one dare to write of grief? To write before resolution, before meaning is wrested from the wound, risks alienating the reader with a narrative deemed unfinished, unhelpful. Yet, to wait, to write years later, risks creating a narrative divorced from the immediacy of pain. What was etched in the raw heat of loss may feel foreign, distant, years hence. Can a grief narrative ever be definitive, or is it destined to remain a work in progress, a testament to the shifting sands of memory and emotion? The role of time, then, is a relentless sculptor, shaping and reshaping the narrative of grief. The writer is not a mere chronicler of loss, but an observer of change, bearing witness to the ever-shifting landscape of grief, acknowledging its inherent ambiguity, its resistance to finality.

In our modern age, there is a tendency to turn grief into content—grief memoirs, viral mourning posts, performative sorrow, curated vulnerability designed for engagement. Social media rewards spectacle, turning raw sorrow into something digestible, shareable, fleeting. Self-help gurus promise tidy solutions, repurposing grief as a stepping stone in the relentless pursuit of personal growth. Even the therapy industry, with its language of closure and healing journeys, can reduce grief to something linear, manageable, marketable. This commodification of grief raises uneasy questions about authenticity and audience consumption.

Yet, even in communities rife with clarion calls of ‘it’s okay to not be okay’ and ‘not everything happens for a reason’ and ‘Let them/me/you’ and ‘as long as my story helps one person then the suffering is worth it,’ there exists a subtle, often unspoken demand. For all its forced and often weaponized empathy, the digital world still expects your grief to do something to you, or at the very least that you should be doing something with it. What’s the point in feeling all your grief if you aren’t going to make it useful for someone else? The ambivalence is palpable: you are urged to feel just as you do, yet also required to transform your pain into something productive, something that serves a greater purpose.

When sorrow is packaged for clicks and retweets, when algorithms prioritize the most dramatic expressions of pain, where does that leave the writer who seeks to articulate something real? How does the writer navigate the space between genuine expression and the potential for their grief to be exploited, consumed, and ultimately, trivialized? The line between personal catharsis and public spectacle blurs, leaving the writer to grapple with the ethical implications of sharing their most vulnerable experiences in a world that often treats suffering as a commodity and attention as currency.

VI. Conclusion: Writing Grief as an Act of Defiance

The challenge of writing about grief is inescapable. Grief, by its very nature, resists finality. It is a shape-shifting entity, constantly evolving, defying any attempt to capture it in a static form. Any attempt to write about grief will, in some way, be a failure, a testament to the limitations of language and the fluid nature of sorrow.

Even in its imperfection, the act of writing grief is an act of witnessing, a refusal to let absence go unspoken. It is a way to honor the memory of those we have lost, to give voice to the enduring impact of their absence. Writing about grief is an act of defiance, a way to reclaim agency in the face of uncontrollable loss.

Perhaps, then, we should return to the surreal anecdote from the introduction, the antique music box and the fading memory of a grandmother’s garden. Now, with a shift in perception, we understand that the blurring of the garden, the wavering melody, the distant echo of her humming are not signs of failure, but rather, testaments to the ever-shifting nature of grief. They are reminders that grief is not a fixed point, but a journey, a process of constant transformation. The impossibility of fixing grief in words does not diminish the necessity of trying. It is in the attempt, in the act of bearing witness, that we find a measure of solace, a way to honor the enduring power of memory and love.

And so, we write not to conquer grief, but to walk alongside it, knowing that in the very act of tracing its elusive contours, we affirm that even in the face of loss, the human spirit endures, forever seeking, forever remembering. Because in the end, grief is not the absence of love—it is love’s echo, reverberating long after the world believes it should have gone silent.